Recently, we spoke to the firm as they continue their 125th anniversary celebrations. We discussed their renowned history, their impact on Detroit and the world, and what they see for the future of Albert Kahn.

Q: What sort of impact has Albert Kahn (Albert Kahn Associates, Inc.) had on the city of Detroit?

Albert Kahn Associates has dramatically shaped the development of the city of Detroit, perhaps more than any other firm. The Kahn office began at a time of incredible growth of the city, designing hundreds of structures that would become nodes for further community development. Today, the firm is actively involved in the rebirth of the city, working alongside our clients and partners to design and engineer environments that anticipate the community’s needs for generations to come.

The Clayton International Lobby in the Detroit News Building.

The Clayton International Lobby in the Detroit News Building.

Several recent examples include creating a new riverwalk amenity out of miles of neglected land along the Detroit Riverfront, setting the standard for other cities and design firms to follow. Kahn also led the first two large (760,000 square feet and 1.2M square feet) adaptive reuse programs in the city, with the conversion of the historic Argonaut Building into the CCS Taubman Center Design Education, and the GM Building into Cadillac Place for the State of Michigan. Adaptive reuse projects to inject new life into iconic structures have become a passion for the firm. Other recent examples include readapting the Detroit News Building, and we are currently working with CHASS on readapting a historic Kahn branch bank. Similarly, the firm has led the renewal and revitalization of COBO Hall Convention Center into the TCF Center, opening the building to the gorgeous waterfront and re-engineering massive sections of the building. We remain involved in the continued renewal of the Detroit Opera House, enabling the old structure to attract and serve new audiences’ needs, among other projects.

Hundreds of Kahn structures once dotted the city. From sprawling industrial complexes to some of the city’s earliest skyscrapers, to cutting edge modern designs that won international recognition, the firm remained intrinsically linked to the development of the city. Some historical examples include:

- Iconic Detroit buildings like the National Bank of Detroit (Now the Qube), General Motors Building (now Cadillac Place), Belle Isle Aquarium and Conservatory, Detroit News Building, and the “Building of the Century,” the Fisher Building.

- Industrial complexes like Packard, Ford Highland Park, Russell, Chrysler Jefferson Plant, among many others.

- Hospitals like the former Children’s Hospital, additions to Henry Ford Hospital, Sinai Hospital, and original buildings along the DMC’s current property.

- Office buildings like the Detroit Free Press Building, Argonaut Building, and Kresge Building, among others.

- Social clubs like the Detroit Athletic Club, Detroit Golf Club, and more.

- Stunning mansions across the city, including the Siegel residences in Boston Edison, homes in Indian Village, and more.

- Automotive sales and service buildings, such as the current home to MoCAD.

- Proliferation of branch banks across the city like the Detroit Savings Banks.

We recently created an interactive map of Kahn projects on our website: albertkahn.com. We have a few hundred listed so far, but we plan to continue to build this out.

Albert and his family were also extremely active in the city. Albert and his brother Julius started the Trussed Concrete Steel Company (which patented the “Kahn System” for reinforced concrete), Albert and Ernestine founded the Kahn Realty Company that leased retail space to small buildings and startups, Albert and his family were active in the Jewish community in Detroit. They were also integral in the Detroit Institute of Arts, perhaps most famously for recommending Paul Cret as the museum’s architect and bringing Diego Rivera to the city.

Q: In your words, what is the “Albert Kahn Legacy” – what should people take away most from his life and his work?

125 years of practice and service to our clients—the firm is proud to be thriving over 78 years after Albert’s death. The Albert Kahn legacy has never been about one person—that is what people need to understand about Kahn. Unlike other, shall we say, “Starchitects,” Albert credited his team (which included hundreds of men and women at any given time) for the firm’s success. Each and every project was and continues to be the product of many individuals. That lesson in teamwork, collaboration, and humility is one that has carried through to the current firm.

Q: What practices set forth by Kahn are still implemented today?

The most important aspect of the firm’s practice is “speed to market” (time is money), as the organization of the firm (architects and engineers) was created to achieve this goal. The client’s needs and goals drive every aspect of the firm.

Albert Kahn is credited with starting one of the first full-service architectural and engineering firms in the country. Architects and engineers were organized together in one location, or firm, because that helped meet the client’s needs. By having multidisciplinary teams in the office, each collaborating on their respective elements of a project, the firm was able to cross-pollinate innovations from one market to another, produce better quality design solutions, and deliver more projects quicker, saving clients time and money. Collaboration is a critical element to successfully developing complex projects in amazingly short periods of time.

Today, the firm prides itself on its collaborative spirit, speed to market, ability to see the big picture without losing sight of the details, and depth of expertise from decades of complex large and small projects across sectors.

Q: What was the most innovative technique used by Kahn?

The Collaborative Design Process, which leads to innovation in multiple arenas. Today, we continue to work with suppliers, design partners, and clients to develop innovative design and engineering solutions. Inside the Polk Penguin Conservation Center, for example, our engineers used their automotive and industrial expertise to design a mechanical system that could clean the habitat in an efficient and safe way never before seen in the Zoo/Aquarium arena. This cross-pollination and innovation is a direct result of the collaborative design process.

The Polk Penguin Conservation Center at the Detroit Zoo.

The Polk Penguin Conservation Center at the Detroit Zoo.

Sometimes this process involves life-sized mock-ups and role-playing. While designing the recent Center for Care and Discovery at the University of Chicago Medicine, the team and clients questioned, tested, and reinvented the standard hospital design to increase efficiency while delivering a therapeutic healing environment for all. Initial design planning began with four-week-long “Kaizen Events,” or interactive workshops to test patient room layouts, nurses’ stations, and support spaces.

Inspired by the Toyota Production System, often used in manufacturing, this concept organizes the interactions of individuals and supplies to minimize waste and cost. A team of approximately thirty frontline professionals was assembled, including physicians, nurses, support staff, and Kahn designers, to test designs in full-size mock-ups. Teams acted out various scripted regular care and emergency procedures within the spaces and chose a unique new design layout that proved to be the most efficient and effective for both patients and their caregivers.

The Polk Penguin Conservation Center at the Detroit Zoo.

The Polk Penguin Conservation Center at the Detroit Zoo.

This practice builds off of a rich legacy of collaboration. During the earliest years of our firm, the collaboration between Albert and Julius Kahn, his brother, led to the development of the Kahn system for reinforced concrete, which dramatically changed the way buildings were designed and engineered. For example, this reinforced concrete allowed for fewer structural columns throughout and greater expanses of glass along the building envelope. This was the first of many innovations by the company. To solve a new problem presented by a client or project, often the firm would work directly with makers, inventors, and tradespeople to develop one-of-a-kind solutions or processes. Eventually, these project-specific innovations forever impacted the building industry, as seen by several patents held by the firm including long span truss construction, interlocking building blocks, the development of a multipurpose wall/roof tile, among others. We continue to collaborate with design and engineering partners to invent new ways to solve specific challenges.

Q: How have the firm’s practices been modified over the years?

Today the firm is still based on the model of multidisciplinary experts collaborating on each project, using the latest computer technology and software. The firm has always been on the cutting edge, and sometimes bleeding edge, of the hand-drawn to Building Information Model evolution. However, as the firm has evolved and technology has advanced, our individual roles have morphed. For example, we no longer have multiple draftsmen that trace and retrace various elements of a drawing by hand. Instead, a team works together through several software programs to produce a virtual model for each project.

Renovations, restorations, and adaptive reuse are playing a much larger role in the firm's practice than in the past. As society recognizes the ever-growing importance of sustainability for our planet and our future, our firm advocates for readapting historic structures, the highest form of sustainable design. Giving these iconic structures a new life through preservation and adaptive re-use preserves that vital link to a broader cultural narrative while positioning communities to reinvent themselves and remain relevant.

We are currently working on three city blocks of urban mixed-use in downtown Erie, Pennsylvania. Approximately seven 1840-1890 buildings are being rehabilitated using historical records and photographs. Our team is saving and preserving what can be salvaged while working with partners to create modern elements inspired by the original photographs. Inside, engineers are making sure that the building will be structurally sound while integrating the comforts of today through custom-designed mechanical, electrical, and IT solutions. These formerly underutilized structures will feature much needed residential apartments, office space, retail and start-up space, restaurants and specialty food markets, along with other one-of-a-kind amenities.

Kahn is preserving historic structures’ identity and character while designing infill buildings that thoughtfully respond to the surrounding structures, melding old and new without overpowering—creating a balance that responds to Erie’s past while looking to future needs and desires.

The Fisher Building.

The Fisher Building.

Q: How would you say the building enclosure has changed over time?

We have been actively involved in changing the focus of the building enclosure to respond to contemporary issues. Today we consider the psychological aspects of the designs we create, of which natural light and views to nature are extremely important. The color of light and the materials we choose have a lasting impact on our client’s organizations. Now, we are employing recycled and sustainable materials for the exterior skin, incorporating smart lighting solutions that respond to the availability of natural light with light sensors and using advanced building monitoring systems to promote efficient and healthy interior air quality.

There is also a renewed interest in a higher level of indoor air quality to mitigate COVID which challenges building HVAC systems and the building envelope. Maintaining indoor humidity levels between 40-60 percent RH helps to mitigate virus particulate. The upper limit is a recommendation not to exceed during summer months and the lower limit is the recommended winter humidification set point. This level of winter humidification is much higher than has been designed to historically and is difficult to achieve without the potential for condensation issues. Building renovation strategies have been developed to help achieve these new humidity targets. New construction envelopes will need to be designed to achieve the thermal performance required to maintain higher target humidity levels.

What we do today builds off of a long tradition of innovation to shape the user experience of each environment. Some of the earliest Kahn buildings were designed to self-ventilate through roof monitors and operable windows, while harnessing natural light to reduce demand on artificial lighting. Each of these design decisions impacted the building enclosure and positively changed the experience inside the space. As time went on and the need developed, Kahn buildings housed some of the most advanced mechanically controlled environments, allowing for the use of alternative exterior materials to improve energy efficiency. And today, we see a combination of old ideas and new technology to allow for the visual and psychological connection to the outside without sacrificing efficiency or comfort.

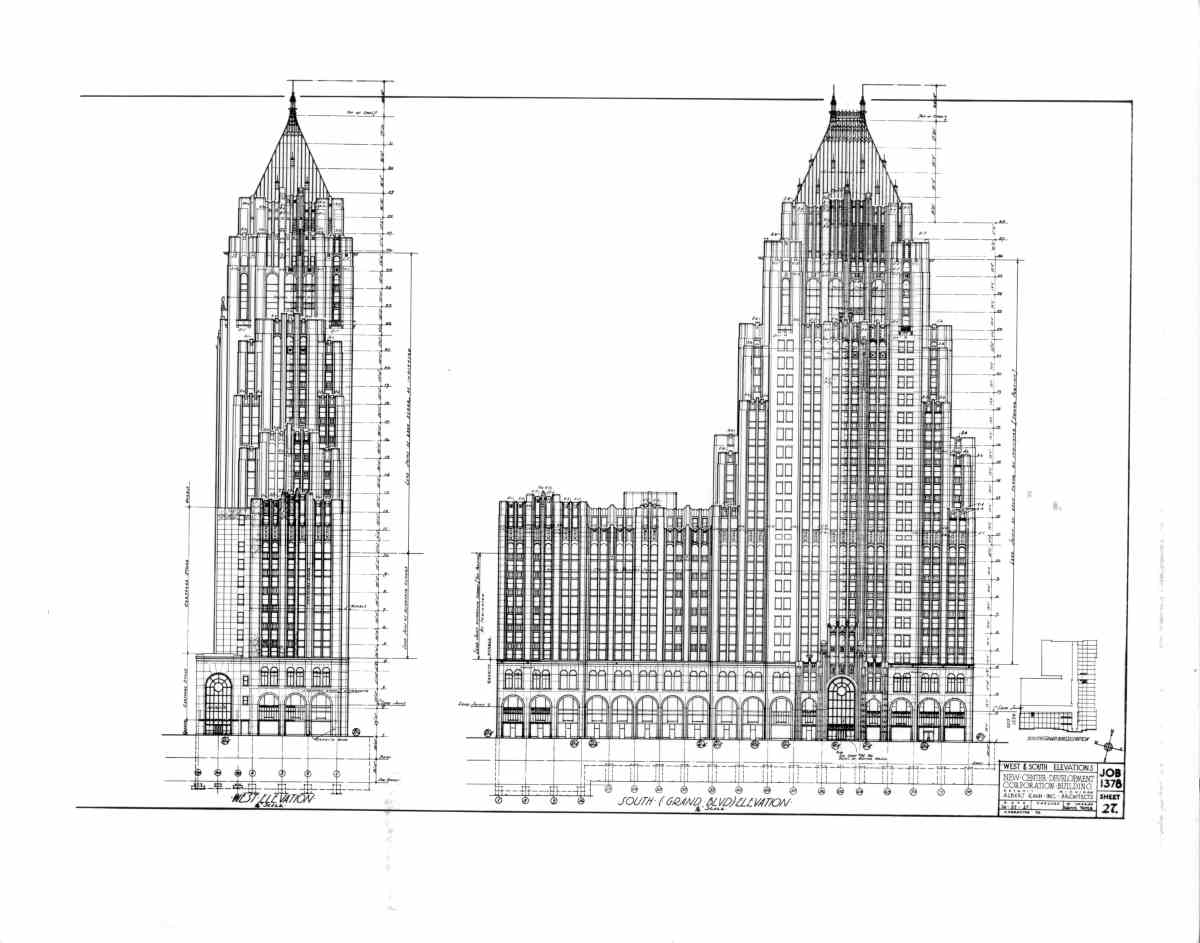

The Fisher Building, West & South Elevations.

The Fisher Building, West & South Elevations.

Q: How has Kahn had an impact on this change? Not just locally, but globally?

When the firm began implementing steel-reinforced concrete, the structural support of the building began to change and allowed greater flexibility of the exterior envelope. Kahn was then able to incorporate larger windows because the weight of the structure was diverted from the exterior, carried instead by fewer steel-reinforced concrete columns and floors. The use of large operable windows became a hallmark of Kahn-designed buildings and created work/live spaces that were more healthy and productive for occupants. Over time the firm continued to investigate innovative materials (such as steel sash, long span steel trusses, prefabricated panels, among others), which influenced modernism and architects around the world.

The firm continued to innovate and find new materials that changed the look and function of the building enclosure, while prioritizing the user experience both inside and outside of the building. Kahn completed projects for clients on 6 continents, which impacted the development of surrounding communities.

Today Kahn designers, architects, and engineers think about the life of the buildings we create after their immediate life, or “cradle-to-cradle” thinking. Sustainable practice and regenerative design at Kahn encourages development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Existing buildings in the “rust belt” of the US that are fast approaching dilapidation or demolition are a mine of raw materials for new projects, for instance. Renovation and restoration reduces the consumption of building materials, resources, energy, and water needed for new construction. There are cultural benefits as old buildings physically link us to our past and become a part of our heritage.

Q: How has he influenced the modern movement overall?

Before modernists championed "form follows function," Albert Kahn brought that notion to life. And this concept continues to guide the firm today. Key historical projects like the Highland Park Plant (1909)—nicknamed the ‘Crystal Palace’ with its expansive glass walls, was one of the forerunners to the modern movement. Here, the building's structure is identifiable in the reinforced concrete columns that remain visible on the exterior. In its stunning simplicity, its innovative use of steel, brick, and glass, and its new aesthetic principle of form following function, the Crystal Palace is thought to have inspired the work of Walter Gropius in his 1914 Faguswerk and influenced the development of European Modernism.

Later projects, such as the Glenn Martin Plant (1937) with its never-before-seen use of 300-foot trusses, pushed this development of universal space. Universal Space is a term that was made most famous by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to describe a long-span, single-volume, flexible structure. This expansive space provided incredible flexibility, whether that be for manufacturing or other purposes. Modernists visited the Highland Park Plant and other Kahn projects, and Mies van der Rohe even incorporated the Kahn-designed Glenn Martin Plant into his class lectures.

We are driven to see the Kahn building legacy in full use, perhaps with different functions (industrial to residential, office to educational, laboratory to design studio). The flexible Kahn loft, or “Universal Space” can nearly be used for any building type.

Q: Is there anything about the building process today that you think Kahn would have liked to see changed/modified?

Albert was known to appreciate the individual talents and expertise of each artisan involved in the building process. If he were around today, he might be disappointed to see the diminished role of artisans and craftsmen in the building process. However, he would likely appreciate the continued progress and advancement, especially the use of new technology to produce novel environments.

Q: How would you say the firm honors him in their designs today?

Albert was one of the most versatile architects, and he started a practice that could do it all. The firm drew from a rich history of design vocabularies to deliver a project that exceeded their client’s vision. When no vocabulary existed for what a client described, Albert and his team used science, engineering, and the latest technology to develop something new. He was a pioneer of the concept: Form Follows Function. Knowledge of the past and the ability to draw from today's interdisciplinary innovations enable our teams to continually ask, “what if?” Remaining committed to our clients, our teams foster a culture of exploration, problem-solving, and collaboration. Together, they help define the innovations of tomorrow.

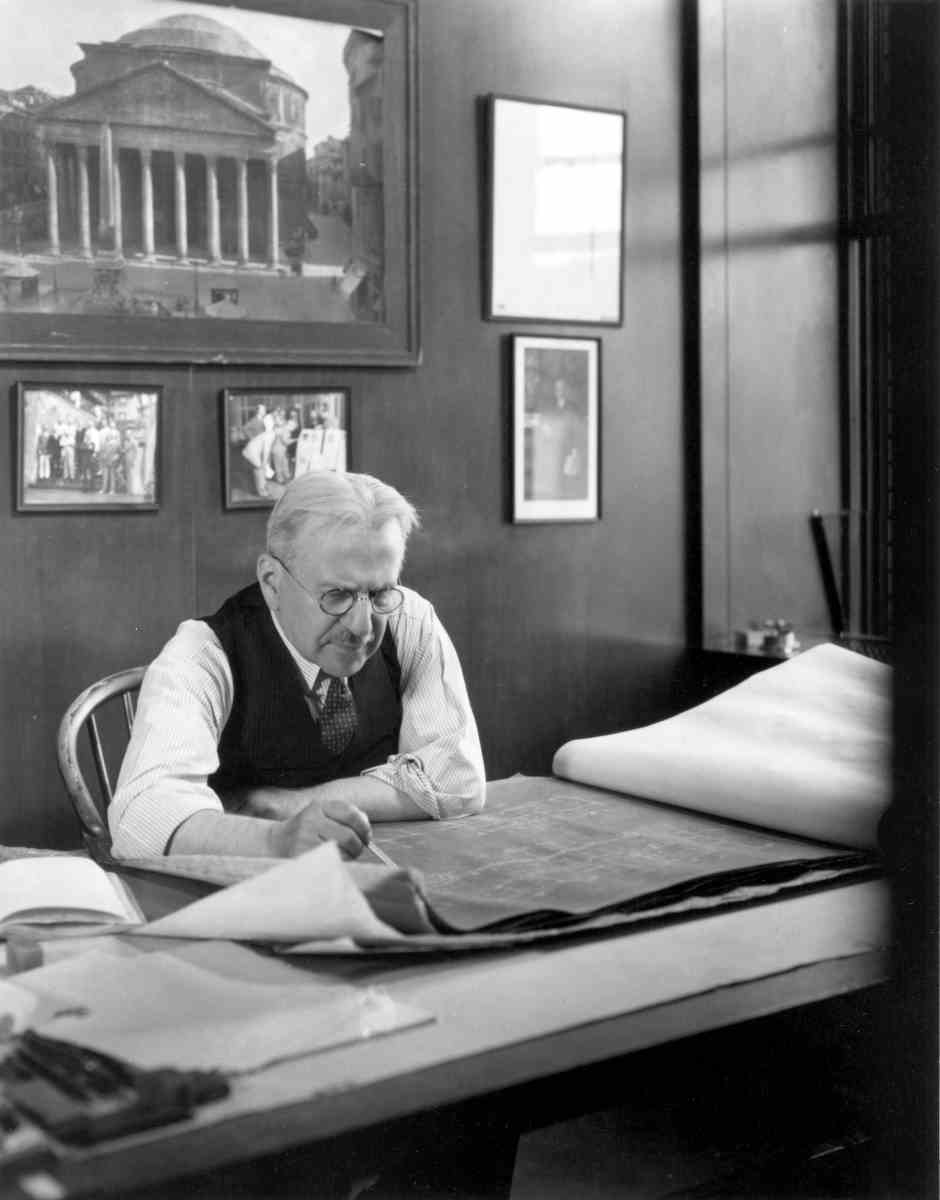

Albert Kahn.

Albert Kahn.

Following our strong industrial legacy, we have recently led the design of 5 million square feet for start-up Vinfast in Hai Phong, Vietnam, which will become Vietnam’s first auto plant, along with 1.6 million square feet of manufacturing facilities for Volvo near Charleston, South Carolina.

Early Kahn factories utilized sustainable design strategies to ventilate and light the shop floors naturally. Today, Volvo Cars’ first North American Manufacturing Facilities is on its way to becoming a LEED campus, with four main buildings expected to achieve LEED Silver. This design-build project with Yates Construction stretched over 1.6 million square feet and was completed in record time due to a comprehensive masterplan, collaborative team members, Kahn’s macro to micro experience, and in-depth process understanding. Sustainable design was integrated into the entire campus from protected areas that restore the natural habitat, reducing light pollution, creating bio-swales and permeable landscapes, to recycling water for irrigation. Anticipating the future of electric vehicles and alternative modes of transit, vehicle charging stations, bicycle storage and links to local transit were all incorporated into the campus.

Blending Volvo’s European ideals with American manufacturing technology results in a high-tech, functional aesthetic. On the exterior, alternating grey and white insulated metal panels decrease in number and spacing to simulate movement and speed, mirroring the product produced inside. This design links each of the buildings, while providing energy-efficient facades. Windows allow natural light to filter through the buildings, reduce demand on artificial lighting, and bridge the office and shop relationship. The office building includes a large cafeteria and outdoor garden café creating a respite for all employees. Designed as an urban café with wood and metal accents, these spaces distract from the intense work requirements. Low emitting materials, recycled content, and locally sourced materials were installed in each building. Buildings on campus are designed to utilize energy over 30 percent more efficiently than required by ASHRAE, due to thermally efficient building envelopes, efficient mechanical and electrical systems, and intended operational conditions.

Q: How many buildings, while he was alive, did he design?

During Albert’s life, he completed approximately 20,000 projects—not all of these were buildings, however. The firm was commissioned to complete an incredible variety of projects, from monuments and multistory buildings to entire industrial campuses. They were often asked to renovate an existing building to make it more efficient or solve a problem another architect was unable to address.

The Kahn firm was unique because it had the full breadth of architects, engineers, designers, planners, and project managers under one roof. This allowed them to accomplish more and provide a broader range of services to clients—something that the firm still maintains 125 years later.

Q: On average, how many projects does Albert Kahn Associates work on per year?

Our workload varies from year to year but on average we have been working on 100-130 projects a year, translating to about $500-750 million in construction costs.

The firm continues to drive future innovation and create environments that better position individuals, companies, and communities for the future. The COVID-19 pandemic is evidence of the need to design flexible spaces to adapt and accommodate change. The pandemic has shifted the way we live and interact; and teams have adapted to address timely concerns in each of our markets. For instance, within healthcare, Kahn has led numerous renovation projects to transform underutilized spaces to vital procedure spaces, allowing hospitals to efficiently upgrade specific areas to address immediate needs and extend the life of their building.

Engineers and architects are working closely with clients to create flexible and safe office environments that inspire creativity and collaboration—whether that is in person or virtual. Designing to aid the clients’ collaborative process and culture and anticipate the need for flexibility has changed how we create physical space. Kahn's continued work with Erie Insurance in Erie, Pa., has been expanding its headquarters to meet its growing personnel needs. When the pandemic hit, they went back to the drawing boards and created solutions that mitigated the virus's spread, including spaced individual workstations, one-way corridors, rooms that accommodated virtual and socially-distant in-person meetings, and proper mechanical solutions that filter out viruses and contaminants. When the coronavirus is a thing of the past, the floorplan of the building will be able to adjust and be rearranged to accommodate a variety of workstyles, including space for concentration, collaboration and more.

The exterior design and massing reveal the balance between fixed concentrated office work areas and collaborative zones. The collaboration areas are represented by cantilevered and angular glass curtain wall panels with a random mullion pattern emphasizing the unscheduled nature of open collaboration. The fixed office areas are represented by strip widows respecting the modularity of the structural system and the nature of concentrated work. These areas are marked by traditional brick patterns, glass, and stonework inspired by the existing campus architecture.

Kahn remains actively engaged with clients across all markets to ensure that they anticipate their future needs and understand the trends impacting their business. This was a lesson passed on from Albert’s time, and the few examples here are some of the ways Kahn is positioned for the next century.

---Albert Kahn Legacy Foundation---

This year also marks the launch of the Albert Kahn Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit organization committed to preserving and celebrating Albert’s legacy and the firm he founded. While Albert Kahn Associates focuses on the future of the built environment for our clients, the Foundation will be there to educate and provide access to perhaps the most extensive archive of an incredible firm. To learn more, visit AlbertKahnLegacy.org.

.jpg?height=200&t=1709237575&width=200)