Every air conditioning unit that uses vapor compression refrigeration contains chemical refrigerant mixes that absorb and release heat to enable a cooling effect through heat transfer.

Some of the most commonly used refrigerants include the following:

- Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), such as R-12, are high in ozone depletion and global warming potential. In order to address ozone depletion, CFCs were completely banned from production or import into the US in 1996 under the 1987 Montreal Protocol.

- Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), such as R-22 (Freon). Although less damaging to the ozone than CFCs, these refrigerants are still quite high in global warming potential. Under the Clean Air Act the US Environmental Protection Agency has mandated that R-22 no longer be manufactured or imported into the country.

- Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), including R-410A and R-134a, have served as the primary replacement to CFCs and HCFCs because they cause much less ozone depletion. However, HFCs still exhibit a high global warming potential.

Defining "global warming potential"

Refrigerants have a relatively low boiling point compared to water. Generally, if refrigerants are exposed to outdoor conditions, they will vaporize into the environment. Like carbon dioxide, these refrigerant vapors are considered "greenhouse gasses" and will tend to trap heat and induce a greenhouse effect in the atmosphere. In fact, HFCs - the de facto refrigerants in the industry today - may be thousands of times greater in global warming potential than carbon dioxide.

Comparing the GWP of common refrigerants

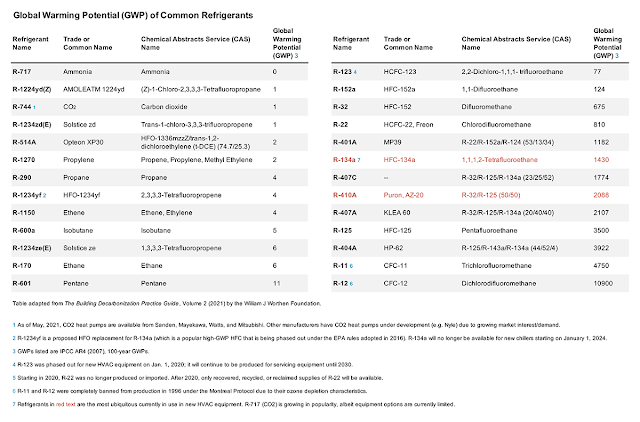

The table below frames the relative global warming potential (GWP) of common refrigerants. The higher the GWP value, the more potential the particular refrigerant mix has to warm the Earth compared to carbon dioxide (which is the baseline listed with a GWP of 1).

Table: Global warming potential of common refrigerants. Adapted from The Building Decarbonization Practice Guide, Volume 2 (2021) by the William J Worthen Foundation. |

Refrigerant management is an extremely high priority

Research has shown that the fluorinated gases widely used as refrigerants today have a potent greenhouse effect. Managing leaks and disposal of these chemicals can avoid enormous amounts of greenhouse gas emissions being released from buildings and landfills. Because of this, many countries, including the US, have regulations governing the handling and disposal of refrigerants. According to the research conducted by Project Drawdown, improved refrigerant management could reduce/sequester the equivalent of 57.75 gigaton of carbon dioxide by the year 2050 - making it one of Project Drawdown's highest-impact solutions to address global greenhouse gas emissions.

Alternative refrigerants and the phase-out of HFCs

In October 2016, representatives from over 170 countries met in Kigali, Rwanda, to negotiate conditions to phase out HFCs. Through an amendment to the Montreal Protocol, the international community will phase out HFCs - which began with high-income countries in 2019, with some low-income countries beginning in 2024 and others in 2028.

Achieving the HFC phase-out will require economic and effective HFC substitutes. Various substitutes are already on the market, including natural refrigerants such as propane (GWP of 4) and ammonium (GWP of 0).

Scientists estimate the Kigali Amendment will reduce global warming by nearly 0.5 °C by the end of the century. However, the bank of HFCs will grow considerably before all countries halt their use. Because 90% of refrigerant emissions happen at end of life, effective disposal of HFCs currently in circulation is critical.

There is no silver bullet to addressing climate change, but improved refrigerant management and the rise of alternative refrigerants will be vital components of a comprehensive solution.